There is a truly fascinating and entirely unexpected history to be told about a small institution which has always punched way above its weight and which lies at the heart of British history.

Sidney is a very well-kept secret - whether it's our Nobel Prize-winners, Elizabethan brickwork, charming Cloister Court, the haunting Chapel, exquisite rococo Hall, medieval cellars, or beautiful ancient gardens - they all lie behind a self-effacing wall of Roman cement.

Sidney Fellows and students from 1596 have made a huge impact on all aspects of the nation's culture, religion, politics, business, legal and scientific achievements. It has also found time to produce soldiers, political cartoonists, alchemists, spies, murderers, ghosts and arsonists as well as media personalities, film and opera directors, a Premiership football club chairman, best-selling authors, the man who introduced soccer to Hungary, the 1928 Grand National winner and, so they say, Sherlock Holmes. And let's not forget the University Challenge Champions of Champions, 2002.

If you wanted to study the history of Britain over the last four hundred years, you could do worse than study the history of Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge.

- Foundations

-

Before Sidney comes the story of the Grey Friars, or Franciscans, who inhabited the site for nearly three hundred years before the violent religious Reformation which led to Sidney's foundation as an explicitly protestant seminary. Excavations in the 1950s revealed traces of a huge complex of buildings, a lay graveyard complete with skeletons now reburied, bucket-loads of superb shattered stained glass and a massive Saxon jar. The cellars housing Sidney's wine below Hall Court are surviving medieval structures from this lost world.

As far as the College foundation is concerned there are still many unanswered intriguing questions - about the Foundress, Lady Frances Sidney, aunt of the famous poet Sir Phillip Sidney, and her life with the top courtier and soldier the Earl of Sussex, her role at Elizabeth's court as advisor and patron of literature and music, her homes in Bermondsey near the royal palace at Greenwich, and at the magnificent New Hall at Boreham, Essex, close to the Mildmay family who founded Emmanuel, a sister protestant college. What links were there between these dynasties and why did Lady Frances want to found a college in Cambridge at all?

Lady Frances's will was written just after the Armada, five years after her husband's death (he had been a loyal catholic under Mary and a fierce rival of Leicester and his protegé, Frances's nephew, Sir Philip Sidney). Was it her idea to leave a small sum to found a College, or was it an idea generated under the powerful influence of her theological mentor Archbishop Whitgift and his circle? Whitgift was a moderate Calvinist and cruel enemy of radical puritanism who nevertheless wanted a serious transformation of the training of English priests - Sidney would have been an ideal opportunity to support this as an 'advance guard' in the creation of a powerful new nation.

What exactly were the accusations against Lady Frances by those 'complotting' her ruin, as she put it, in the fraught 1580s, which made her want to leave grand physical monuments, (the funeral one at Westminster Abbey as well as the 'goodly and godly' one at Cambridge which interests us), to help repair her reputation? A libellous pamphlet by Arthur Hall, a notorious rogue MP, who tried to woo her was burned by her nephews the Harrington family in 1588. How much were Renaissance ideas of personal honour, evident in her and the College's motto, ‘Dieu me garde de calomnie’, motivating her benefaction?

Lady Frances died in 1589 and her will's main executors, supervised by Whitgift, were Sir John Harrington, among other things guardian of the doomed Princess Elizabeth, and the lawyer Henry Grey, Earl of Kent. Without them Sidney would never have been founded. When it was easier to give the money to Clare, as the will allowed, why did they persist against such difficulties as those they faced between the reading of the will in 1589 and St. Valentine's Day 1596 when the deed was signed?

- Roundheads or Cavaliers?

-

Famous as the college attended by Oliver Cromwell there is a question as to whether Sidney was really a 'puritan' college at all, in the sense many take the word to have? One of its first aristocratic students, the glamorous and talented Sir John Harrington, son of the executor already mentioned, was Prince Henry's closest friend and therefore certainly part of the new military, religious and cultural elite in England. But the story is very complex. The inter-related families at the heart of Sidney's early years, the Montagus and Harringtons, both of Northamptonshire, were rising powers in late Elizabethan and Jacobean England. James Montagu, the first Sidney master, was James 1's editor and, like his successor but one, Samuel Ward, one of the translators of the Authorised Bible of 1611, perhaps the key text in the growth of modern English religion and literature and thus of national identity. These men drew around them a remarkable body of Fellows and students in the years before the Civil War: Thomas Gataker, a major classical scholar and puritan theologian who became embroiled in a famous debate about predestination and gambling; the High Churchman and Hebraicist John Pocklington, whose 'Sunday No Sabbath' was burned in 1635; another Hebraicist Paul Micklethwaite, who became a troublesome Master of the Temple; William Bradshaw, who supported the bogus exorcist William Darnell and was author of the important history 'English Puritanism' in 1605; Samuel Ward of Ipswich (no relation), who was a celebrated preacher based in Ipswich and one of Britain's first political cartoonists; Jeremiah Whitaker, the oriental scholar and friend of Cromwell who moderated at the seminal 1643 Westminster Assembly of Divines (and with a wife called Chephtzibah!); the royalist Sir Thomas Adams, founder of an Arabic professorship at Cambridge and Lord Mayor of London; according to Thomas Fuller, the extraordinary preacher Thomas Adams, dubbed by Southey the 'prose Shakespeare of puritan theology' and a major influence on Bunyan; the two related Daniel Dykes, one a puritan divine who refused to wear a surplice, the other a Baptist minister and one of two of Cromwell's Sidney chaplains, who is buried at Bunhill Fields near Daniel Defoe and William Blake.

The list of major figures in English life goes on impressively and certainly gives the lie to any idea of a simply puritan and radical college dominated by Cromwell's ghost and that of his renowned Sidney contemporary and eventual enemy, Edward Montagu, 2nd Earl of Manchester. Indeed, even the devoutly Calvinist but politically conservative Samuel Ward, died imprisoned as a result of resisting his former student's assault on the College's independence in 1643.

Sidney certainly had many hard-core protestants - for instance, exiled students from Heidelberg and displaced Dutchmen, one of whom, John (later Baron) Reede, was to become President of the States General in Holland; a number of early pioneering colonists in America such as the poetical George Moxon and Cromwell's footballing friend John Wheelwright; and Sir John Reynolds, one of Cromwell's finest soldiers who died shipwrecked on Goodwin Sands.

Royalists abound too, however - John Bramhall, Archbishop of Armagh, famous opponent of Hobbes and subject of a major essay by T S Eliot; Montagu Bertie, Lord Willoughby, who bravely tried to rescue his father during the fighting at Edgehill; George Goring, one of the king's most important and daring generals; Edward Noel, Viscount Campden; and, perhaps most extraordinarily, Walter Montagu, author of 'The Shepherd's Paradise', an eight-hour masque for Queen Henrietta Maria in the 1630s, for which designs by Inigo Jones still exist, a spy in France who was imprisoned in the Bastille by Richelieu and who makes an appearance in Dumas's 'Three Musketeers', and a catholic convert who ended up as a revered abbé in France.

Sidney did well beyond religion, politics and war, however, though of course all spheres of life in a small world were inter-connected. Literature is a particularly strong card. Charles Aleyn, the author of historical poems on the battles of Crecy and Poitiers and on Henry V11; Sir Roger L'Estrange, best known as a pioneering newspaper editor, translator of Aesop's Fables, Cicero and Seneca and state censor under Charles 11, was also a rash and brave defender of King's Lynn in the King's cause. On the other side, the poet, dramatist and translator of Lucan, Thomas May, who wrote the unjustly neglected parliamentarian history of the civil war, was disinterred at the Restoration and thrown into a pit; the delightful supporter of Charles 1 Thomas Fuller, one of the greatest literary figures of the seventeenth century, author of the 'Worthies of England' and perhaps the first professional man of letters in England; the Paracelsian William Dugard, friend and publisher of Milton; Thomas Rymer, one of the most important historians and literary critics of the early modern period.

Sidney took a lead in science and medicine too - there were scientific books and instruments, and an ancient calcinated human skull, in the well-stocked library and Master's Lodge which suggest a thriving interest in the 'new philosophies'. The celebrated Bishop of Winchester, Seth Ward, was an undergraduate and graduate, and went on to become a major mathematician and astronomer and a founder of the Royal Society; George Ent, a medic and a founder of the Royal Society and proselytiser of his friend William Harvey's theory of circulation; John Sterne, founder of the Royal College of Physicians in Dublin as well as a professor of law and Hebrew; the mathematician and theologian Gilbert Clerke, who invented the 'spot dial', was ordained as a Presbyterian minister and later became a Unitarian and who laid out the beautiful grounds of Lamport Hall in Northamptonshire.

- After the Storm

-

The Restoration seems to have been the beginning of a deep and troubling change in Sidney's fortunes. In spite of John Evelyn's reference to Sidney in 1654 as 'a fine college', the extraordinarily brutal murder of an undergraduate, George Sondes, by his younger Sidneian brother Freeman, which was a national sensation in 1655, perhaps symbolises some of the troubles ahead. Once the royally-favoured and fashionable college for aristocrats, gentry and ambitious young churchmen, it seemed to suffer somewhat under the stigma attached to its Cromwellian connections. In fact, Cambridge goes in to a decline in the late seventeenth century, and Sidney's rather fallow period until the mid-eighteenth century is not unusual. There were, as ever, financial problems, and the importance within the nation's culture of religion, the heart of the College's meaning, compared with the heroic early years, was beginning a slow decline.

Notable members of the college seem to have been keen on religious and other controversy: Joshua Bassett, the rather unimpressive Richard Minshull's Catholic successor, imposed on Sidney by James 11, who fled overnight at the arrival of William of Orange; the probably insane heretic and denier of Christ's divinity, Thomas Woolston, who became embroiled in a major controversy with other theologians and died in prison; Thomas Baker, the playwright and editor , as ‘Mrs Crackenthorpe’ of the first ladies’ lifestyle magazine, ‘The Female Tatler’; John Gay the philosopher who, in typical Sidney style, more-or-less pioneered Utilitarianism nearly a century early with an essay appended to someone else's book; Bishops Garnett and Reynolds and the notable theologian David Jenner; the judge William Morton who sentenced to death the daredevil French 'gallant highwayman', Claude Duval, in spite of popular protest; and, in the 1740s, Richard Walter, chaplain on Anson's celebrated voyage round the world and almost certainly the editor, and quite possibly in large part the author, of the admiral's best-selling classic account of his adventures in search of Spanish bullion.

Perhaps the most important figure at Sidney in the early eighteenth century was the theologian and moral philosopher William Wollaston whose 'Religion of Nature Delineated' of 1724 achieved huge sales and led to his being one of five British 'worthies', along with Newton and Boyle, sculpted by Rysbrack for Queen Caroline's Hermitage built by William Kent at Kew. Finally, the brilliant and troubled poet, William Pattison, who died at 24 of smallpox and was considered by Pope and others a great talent lost to literature, seems to be indicative of the stop-start frustrations which beset these times at Sidney.

One of the things which helped Sidney, rarely a wealthy college - indeed usually a distinctly impoverished one until perhaps fifty years ago - to climb back to some prominence was the setting up of the Taylor Lectureship in Mathematics in the 1720s, leading to a high reputation in the subject which, via the extraordinary ten out of ten firsts in 1921, continued well into the late twentieth century. As religion began to lose its hold on the wider society, Sidney had to learn to adjust itself to the new prominence of science and mathematics in the post-Newtonian age. Among the distinguished mid-century mathematicians were John Colson, inventor of + and - digits, so I am told, and Samuel Vince, a former bricklayer who became Plumian Professor of Astronomy!

- Placid Men

-

These men were followed by many Wranglers and also distinguished 'natural philosophers' such as the Linnaean Professor of Botany Thomas Martyn, a founder of the University Botanical Gardens, an art connoisseur and populariser of Rousseau for young ladies; Francis Wollaston, the theologian, astronomer and author of the intriguing-sounding 'The Secret History of a Private Man' in 1793; George Wollaston, the editor of Newton's works and close friend of the poet Thomas Gray, and (what a dynasty!) F J H Wollaston, the Jacksonian Professor and natural philosopher who has a remarkable and rather humorous monument by Francis Chantrey at the church in South Weald, Essex.

The second half of the eighteenth century saw some major improvements to a set of buildings which seem to have badly deteriorated since visitors such as Uffenbach and Beeverell around 1700 described an attractive red brick college. The recently (2002) repainted Hall was built by James Burrough within the old Elizabethan tie-beamed room around 1750, and is one of the great Rococo interiors of Cambridge - it is of course a shame that the surviving huge roof is now obsured to view; the Chapel, re-designed by James Essex in the 1770s, was an equally impressive make-over of a plain if evocative seventeenth century religious space, now adorned with a previously unthinkable Catholic altarpiece by the Venetian painter Pittoni. By now the gardens were also appearing in illustrations as among the most beautiful in the university. With only the two front courts, Sidney must have been a wonderful open site to behold, a 'lovers' walk', as it was described - an appropriate description for a college officially founded on St Valentine's Day. Images of the time show Fellows playing bowls in an idyllic garden.

One imagines a small, pretty and friendly college in the Romantic period, from the 1760s until the 1820s, with a talented young Fellowship inclined often to gentle literary and classical interests and concerned with liberal causes: S T Coleridge's talented father, John, who attended as a mature student, (it is something of a mystery why his famous son didn't attend Sidney rather than Jesus, which he didn’t enjoy); Thomas Twining of the tea family was a translator of Aristotle (his 'Poetics' is still available as a classic) and a musician with close ties to Charles Burney; John Lettice was a Seatonian Prize winner in 1764 who wrote his 'Fables' in 1812 and co-translated 'The Antiquities of Herculaneum' and arranged the famous trip to Sidney by Samuel Johnson which nearly led, it seems, to the great doctor becoming a Fellow; Lettice was alos tutor to William Beckford and the accounts of his travels with the wayward young genius make hilarious reading; another Seatonian Prize winner, John Hey, first Norrisian Professor, whose lectures were avidly attended by the younger Pitt and, as he recounts in his wonderful diary, whose wooden false tooth fell out while proposing marriage (!); H W Coulthurst, a young Fellow who helped to pioneer the anti-slavery cause in Cambridge, at a college full of sympathisers such as Weeden Butler who wrote the novel 'Zimao the African' in the 1790s; Weeden's brother, the renowned Harrow headmaster George, who befriended and greatly impressed Schiller and Goethe in Germany and was the butt of Byron’s early satirical verse; the vicar and Seatonian Prize-winning poet Charles Jenner who wrote a popular novel 'The Placid Man' and the play 'The Man of Family' and who died of a cold caught at Vauxhall Gardens; the major classical scholars James Tate, the 'Scholar of the North', described by Sidney Smith as 'dripping with Greek' and Thomas Mitchell the friend of Byron; Cecil Renouard, a Professor of Arabic and archaeologist, geologist and botanist who was a chaplain in Constantinople and excavated at Smyrna; and Jabez Henry, the colonial judge and major legal author.

-

And Then There Was One

-

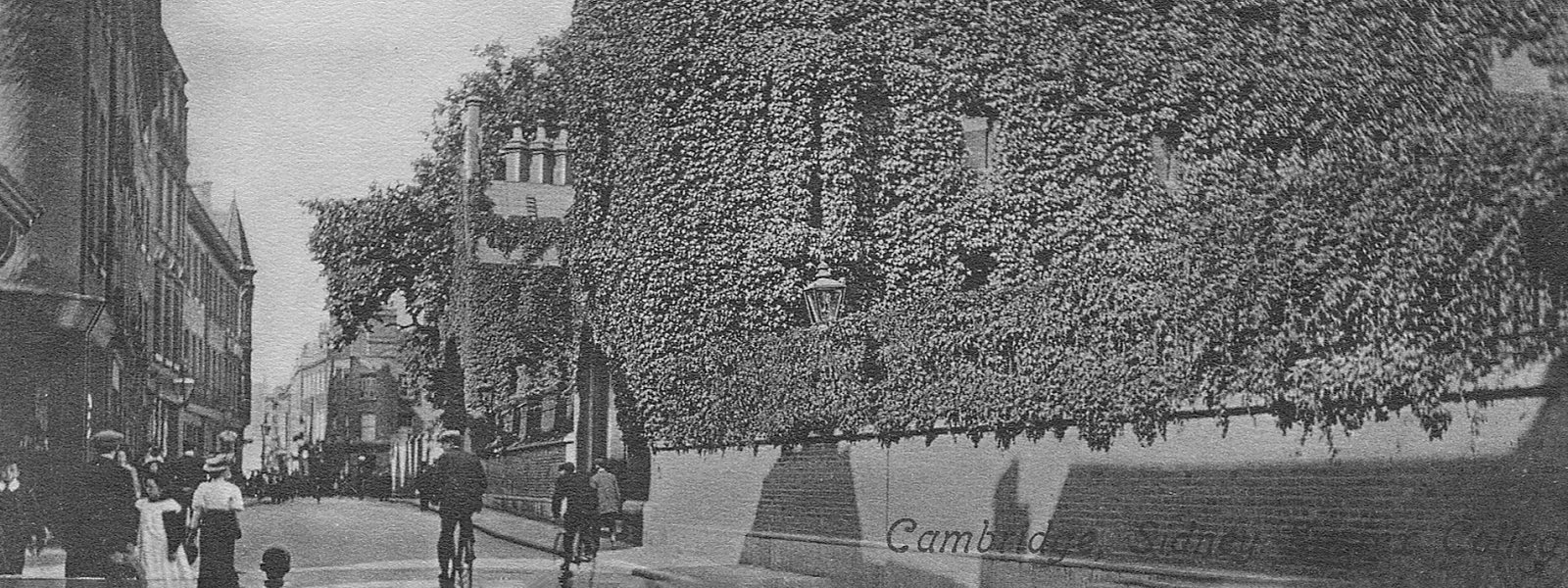

These were good times, in spite of the wars with France which saw the grounds used for training by local troops, and show a college moving confidently in the modern world of scholarship. The arrival of the controversial and clearly over-bearing if dynamic Master William Chafy in 1813, led to an architectural expression of that confidence which still divides opinion. Chafy invited the Whig-connected Jeffrey Wyatt, (later Wyattville by Royal agreement following his extensive work at Windsor), to refurbish the buildings which had been described in 1814 as 'gloomy'. During the 1820s the buildings were reconfigured to produce the present look, with a central front tower and entrance and the 'embellishment' of the old buildings with a layer of Roman cement to give what was then thought to be a medieval/Elizabethan look - perhaps echoing the Sidney ancestral home at Penshurst and Horace Walpole's Strawberry Hill - and made the college a favourite subject for picturesque prints. Later in the century, and for many years, the cement was greatly occluded by masses of ivy giving Sidney an agreeably shaggy look. E H Griffiths in his 'Song' quoted at the head of this piece, claimed that 'we love the dusky buildings where our friends and comrades dwell', suggesting a corporate character which survives aesthetic troubles. The 'ugly duckling' image, compounded by the architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner's dim view of Wyattville's efforts, however, never quite went away - rather galling for porcupines!

Sidney was a very small college in terms of undergraduate admissions for much of the early Victorian period when it became in effect an Anglican seminary. Sidney seems to have had its fair share of ‘bounders’: men such as Frederick Kendall, sent down for trying to burn the College down in 1812; the Prseident of the Union, dandy and con-man, Henry Mathew, who is immortalised as ‘Bloundell-Bloundell’ in Thackeray’s ‘Pendennis’. Sidney also produced a novelist in the Jewish student Samuel Phillips, the Times literary critic whose 'Caleb Stukeley' was a three-volume popular success, and the polymath and friend of Turner and Ruskin, the Rev. W.T. Kingsley. Another polymath, John Clough Williams Ellis, was the friend of the Fellow John Hardy and the two men were founding members of the Alpine Club and completed the historic first ascent of the Finsteraarhorn in 1858. A friend of these men was another ‘massive’ Victorian, Robert Machray, who became Canada’s first Archbishop. George Mason, an undergraduate, took a few years off with his brother to start a new life in Africa and wrote a superb account of his experiences in 1855, ‘Life Among the Zulus’. Others include the astronomer William Scott who founded Australia’s first observatory and the pioneering Anglo-Catholic, Thomas Pelham Dale who was imprisoned for his ‘ritualistic’ high church practices and R.A.M. Stevenson, the art critic and bohemian cousin of Robert Louis who was ‘led astray’ by the Sidney man.

Sidney was also the site, in the Master's Lodge, of a haunting in 1841 which caused a great sensation, a visit by the Prince of Wales for a performance of Mendelsohn's 'Elijah' in the Hall in 1861 and, notoriously, the serving of roast leg of donkey to a group of guests in 1869! We need to know much more about a college during this period whose undergraduate population famously dropped to one and whose Fellows until 1882 were not allowed to marry. There are still many questions about this period - what were the dons' reactions to Darwin, for instance, to the Reform Act and Catholic Emancipation? And how did a 'puritan' college respond so positively to the rise of the High Church that its new chapel, built in the Edwardian era, is the finest and most elaborate modern Catholic-style one in Cambridge?

-

Experimentation

-

The reforms to the university of the 1850s and later, while resisted so fiercely and famously by Chafy's successor Robert Phelps, changed Sidney's intellectual course forever. From the largely theological and mathematical college of the first two centuries or so, it became a power-house in the rapidly expanding medical, natural, physical and chemical sciences, much inspired in this direction by Clough Williams Ellis. John Wale Hicks, later Bishop of Bloemfontein, was typical of the time in publishing books on both doctrine and inorganic chemistry. The laboratories which stood along the Sidney Street wall beyond 'A' staircase, among the first in Cambridge, were the site of a string of important experiments by the world famous metallurgist F H Neville and others such as E H Griffiths until they fell into disuse by 1910 - their renown led Dorothy L Sayers to propose Sidney as Sherlock Holmes's college!. In the real world, Neville, a member of the Society for Psychical Research and much concerned with 'metaphysical speculations' was, following his conversion in 1904, the first ever Catholic fellow at Sidney. Harry Marshall Ward, Professor of Botany, G R Mines an internationally renowned cardiologist and the geologist William Whitehead Watts, were all major figures who helped Sidney become the great scientific force it remains today. Sir William Jackson Pope, a leading figure in stereometry and the investigation of the optical properties of organic compounds, is also now notorious as a pioneer of chemical warfare research during the First World War. All of these developments in Sidney's profile were architecturally matched by the building of Pearson's inspired and charming neo-Jacobean New (now Cloister) Court in 1890, providing more room for the growing numbers of undergraduates.

- Sidney Yet is Young

-

The early twentieth century was to be the time in which Sidney finally began to achieve its potential more fully, echoing in many ways its meteoric rise to prominence in the early seventeenth century. The twentieth century saw the College become almost unrecognisable from its early years. Garden, South, Blundell and Cromwell Courts have transformed the look of the College and allowed massive growth in student numbers on site. Sidney excels academically across the board in most subjects yet retains its unique friendly, informal yet traditional atmosphere.

We have produced four Nobel Prize winners; the College played an absolutely central role in the code-breaking successes at Bletchley Park during the war under the guidance of the maths fellow Gordon Welchman who brought in brilliant undergarduates such as John Herivel who made a key contribution in breaking Enigma; maths has bloomed since then, not least in the 1960s when the world famous inventor of 'surreal numbers' and the addictive 'Game of Life', John Conway, was a Fellow. Among the many distinguished Sidney geologists this century, such as Oliver Bulman, special mention must be given to Harry Whittington and his team who made the extraordinary discoveries about the Burgess Shale popularised in Stephen Jay Gould's international best-seller 'Wonderful Life'; C T R Wilson the visionary Nobel physicist and inventor of the romantic-sounding Cloud Chamber; E J H Corner the botanist; W T Stearn, a Sidney gardener as a teenager who became an internationally renowned botanist; Alexander McCance the world famous nutritionist; C H Waddington the geneticist and art theorist; C F Powell the Nobel nuclear physicist; Harry Emeleus the inorganic chemist; ,Paul Scott the astronomer; the engineers Tom Charlton, Keith Glover and Stephen Salter - the list is impressive.

It's certainly not all lab coats and boffins however. The humanities, beyond Classics, have also come into their own in the last fifty years. History from the 1940s has been a huge success story with Asa Briggs, David Thomson, Derek Beales, Tim Blanning, Otto Smail, John Brewer and Helen Castor among the many names who have acquired international reputations. It is also a subject which has produced some of the country's best known politicians and commentators. In these fields, though not all historians, the familiar figures of politicians David Owen, Ian Lang and Nick Raynsford and journalists Peter Riddell, Andrew Rawnsley, Mark Devenport and Leo McKinstry are all Sidney graduates, as were earlier Frank Owen, the legendary editor of the Evening Standard, Gordon Newton of the Financial Times and Michael Curtis the News Chronicle editor whose brave coverage of the Suez Crisis cost him dear.

In the arts, often through English graduates, we can claim the top film directors John Madden and John Amiel, theatre and opera director the recently deceased Stephen Pimlott, composer Huw Spratling and 'Gothic Voices' maestro Christopher Page who brought the music of the medieval mystic Hildegard of Bingen to the world's attention and in the world of writing, international best-selling sci-fi novelist Stephen Baxter, the novelist Rupert Thomson and 'New Puritan' author Matt Thorne, to name a few.

Indeed, every subject - from the spectacular recent rise of Law to the well-established pre-eminence of Engineering, from Economics to Medicine and Geography - has contributed to the secret life of a College which gets on with things quietly but is also quietly proud of its past and present and confident about its future.